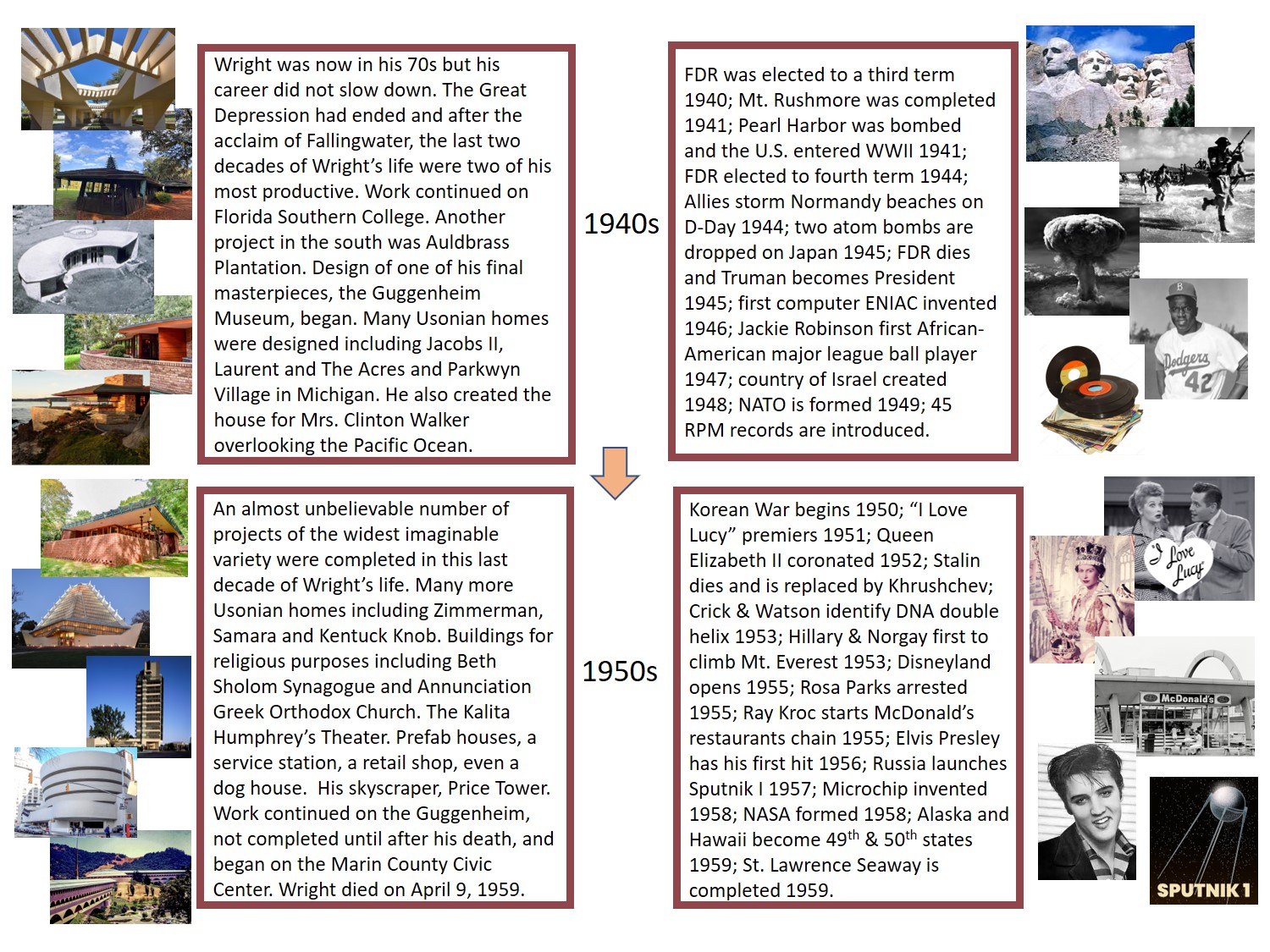

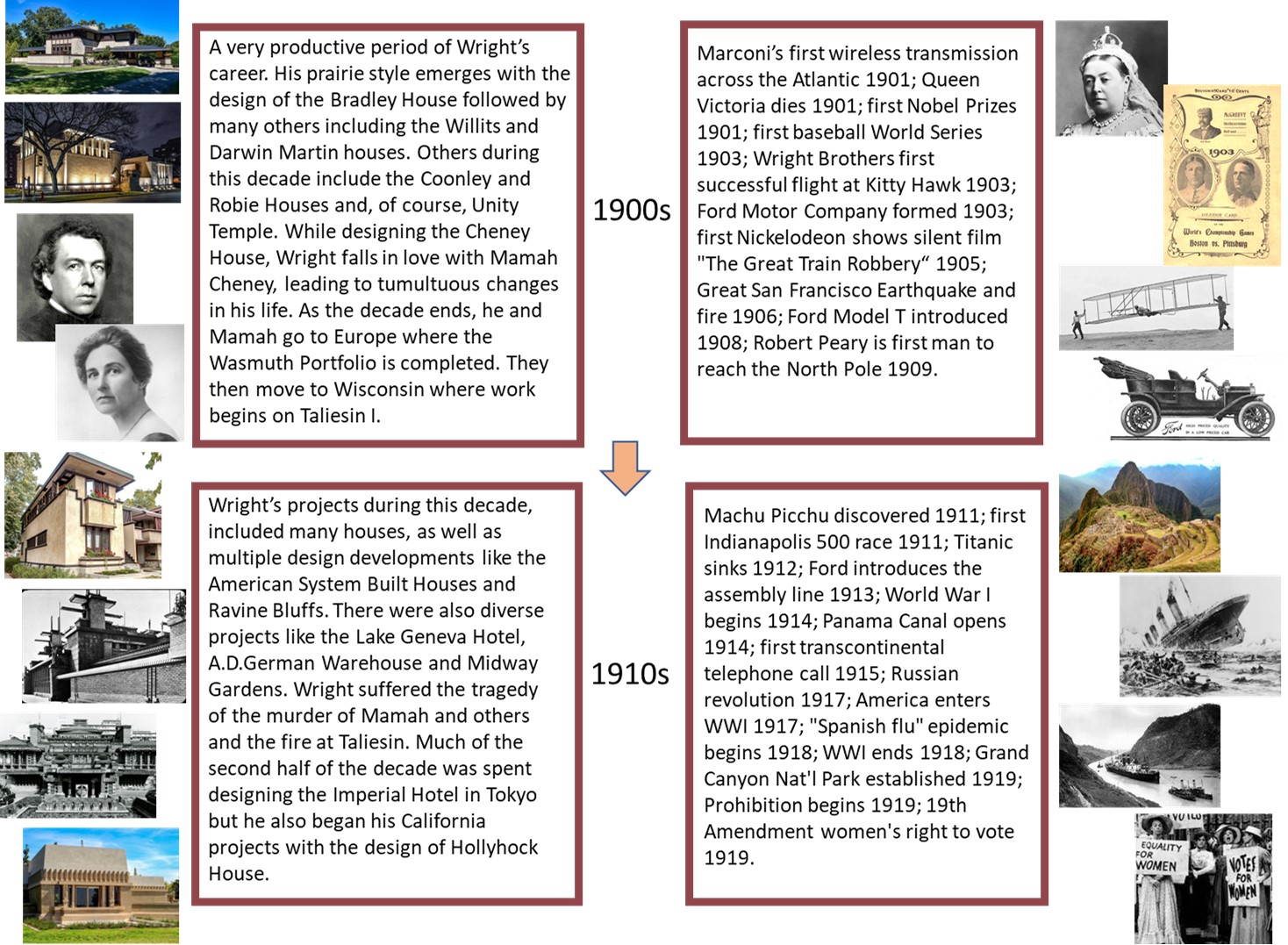

I recently visited Barcelona, Spain and, of course, toured a number of sites designed by the architect, Antoni Gaudi. Gaudi was born in 1852, 25 years before Frank Lloyd Wright was born. He began work on his most famous structure, La Sagrada Familia Basilica, in 1883, about 20 years before Wright began designing Unity Temple. Gaudi completely changed the initial design that had been started by another architect. Sagrada Familia and Unity Temple could not be more different, but they are both beautiful and inspiring spaces designed for religious purposes.

I recently visited Barcelona, Spain and, of course, toured a number of sites designed by the architect, Antoni Gaudi. Gaudi was born in 1852, 25 years before Frank Lloyd Wright was born. He began work on his most famous structure, La Sagrada Familia Basilica, in 1883, about 20 years before Wright began designing Unity Temple. Gaudi completely changed the initial design that had been started by another architect. Sagrada Familia and Unity Temple could not be more different, but they are both beautiful and inspiring spaces designed for religious purposes.

Unlike Wright, Gaudi had a formal education in architecture. However, he was not a good student and failed a number of courses. Upon graduation from the Barcelona Higher School of Architecture, the director is quoted as saying about Gaudi, “We have given this academic title either to a fool or a genius. Time will show.” Like Wright, Gaudi was inspired by nature and his work is considered organic. His curvaceous, highly ornamented designs were controversial and disliked by many (sounds familiar). Both Gaudi and Wright had early experiences at World’s Fairs. Gaudi displayed some of his work at the 1878 Paris World’s Fair, and Wright was involved in the design of the Transportation Pavilion at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago while working for Adler & Sullivan. Like Wright, Gaudi considered every detail and incorporated stained glass, ceramics, wrought iron and carpentry into his designs. Both architects designed furniture.

Like the Gale and Martin families were the source of many projects for Wright, Catalan industrialist Eusebi Güell provided many commissions to Gaudi. These included the mansion Palau Güell and Park Güell, intended to be a development of upscale houses that never materialized. It is now a public park. A collection of Gaudi’s work, like Wright’s, are designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Unity Temple and Sagrada Familia are representations of the genius of these two architects. Building Unity Temple involved some delays and a significant budget overrun, due partially to the contractor’s learning curve with a relatively new type of construction, steel-reinforced concrete. However, it was completed in just a few years. Sagrada Familia, on the other hand, was less than 25% complete when Gaudi died in 1926 and is still under construction almost 100 years later. It had been planned to be completed in 2026 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Gaudi’s death. Delay during the pandemic has put the completion date in doubt. Sagrada Familia is a monumental structure, compared to the comparatively modest size of Unity Temple. When completed, it will be the tallest church in the world.

Designed during the peak of the Prairie style period of Wright’s career and built for a Unitarian congregation, no religious iconography is displayed in Unity Temple and the only ornamentation is the geometric abstraction of the columns along the exterior of the clerestory windows. Gaudi, like Wright, was inspired by nature, unlike Wright, he was devoutly religious, and icons of Catholicism are incorporated extensively on the east and west facades of Sagrada Familia.

While on a totally different scale, there are similarities in the contrast between the exterior and interiors of the two buildings. The transition from the austere, monochromatic exterior of Unity Temple to the warm, light-filled interior, is one of the most compelling aspects of the design. The exterior of Sagrada Familia, although covered in sculptures and carvings, is monochromatic, other than colorful ornamentation on top of some of the tall spires. Inside, while almost overwhelming in its size, it is mostly unornamented. Your eyes are immediately drawn upwards in both sanctuaries. In Unity, long pendant light supports and vertical wood banding draws your focus up to the coffered grid of skylights. In Sagrada, your gaze tends to follow the extremely tall, tree-like columns up to a ceiling with the array of religious medallions surrounded by plaster carvings that look like sunbursts. Both architects used leaded glass effectively, Wright with his signature application of subtle geometric patterns, Gaudi with brightly colored mosaic designs. Gaudi’s color palette in the glass is particularly striking in the soft blues and greens that catch the morning light on the east façade, contrasting with the warm yellows, oranges and reds for the afternoon sun on the west side.

Wright apparently suffered from no chronic health conditions and had a long life, living to age 92. The last years of his life were very productive with a number of major commissions, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York. The museum and a number of the other projects were not completed until after his death. Gaudi, on the other hand, suffered from poor health for much of his life and devoted the last 15 years of his life entirely to one project, Sagrada Familia. In his later years, very unlike Wright, Gaudi lived a very frugal life and dressed in old, worn clothes. This contributed to his untimely death at age 73. He was struck by a tram and knocked unconscious. He was mistaken for a beggar and left to lay in the road for some time and when he was finally taken to a hospital, he was not given the necessary attention. By the time he was recognized, it was too late and he died a few days later.

These brief descriptions and the few accompanying photographs, attempt to illustrate the parallels and contrasts of these two sacred spaces and the men who designed them. However, both structures need to be experienced in-person to truly appreciate these architectural masterpieces.

By Ken Simpson

Looking down the tight, nautilus-like spiral staircase.

Looking down the tight, nautilus-like spiral staircase.  A close-up of one of the austere, geometric figures on the western façade. The view shows how the basilica towers rise over the city.

A close-up of one of the austere, geometric figures on the western façade. The view shows how the basilica towers rise over the city. Windows on the east side in shades of blues and greens that catch the morning light.

Windows on the east side in shades of blues and greens that catch the morning light. Looking up into one section of the interior. The tree-like columns branch out as they reach the ceiling.

Looking up into one section of the interior. The tree-like columns branch out as they reach the ceiling. Eastern façade from the small park across the street.

Eastern façade from the small park across the street.